Moving to Taylor Creek

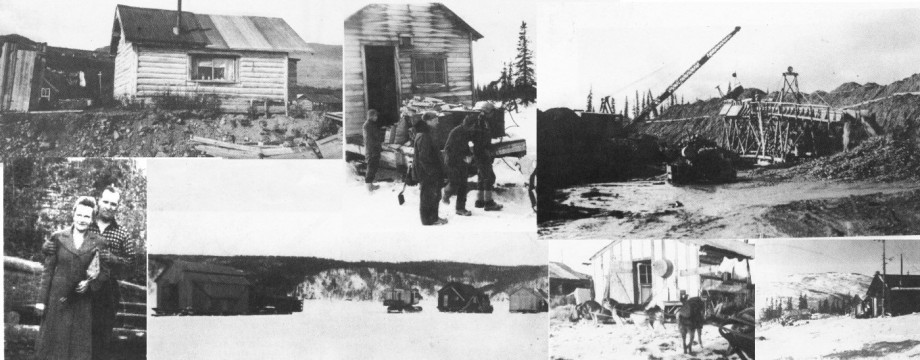

During the summer we made a deal with Nick Mellick in Sleetmute to move our Moore Creek outfit to mine his ground on Taylor Creek, about one hundred fifty air miles south.

During the winter of 1948 Joe and Claire Fejes, and Hildur and I, decided to start a folk dance club. Our first dance was in a private home with a phonograph for music. There were six couples. Each was to bring another couple the next time. Soon the room was too small. We rented the Oddfellow’s Hall and charged admission, then hired an orchestra and a square dance caller. It was a lot of fun and we made many friends. We named it the Fairbanks Folkdance Club, and it lasted for twenty four years. On the twentieth year they had a celebration, at which we charter members were honored.

Hildur had been substitute teaching and in February signed a contract to teach first grade. She got her college degree by attending eight summer sessions at the University of Alaska, two at Cornell, and one year at the University of Washington, finally graduating at the University of Alaska two years ahead of our son Ray.

Lempi and Art both had good jobs in Fairbanks, so I hired a crew, and Inez Pangman (a grand, seventy-year-old lady) for cook, and mined Moore Creek again in 1949, with no better luck.

We had quite a few visitors at the mine. Sometimes bush pilots dropped in for a meal. The mother of one of our men came from Spokane, Washington, to see how her son was doing. Hulda and two of her children, Roy and Sigrid, came from Spencer, New York. Aina and Gus, John Ogriz and his wife Peggy, and occasionally, machinery parts salesmen, flew in.

We made our own entertainment. One morning little Hilda asked her mother how she could catch one of those pretty little birds that were walking around by the mess house. Hildur told her to go ask Inez for a little salt to put on the bird’s tail. Inez asked what she wanted the salt for, and had a hard time to keep from laughing. A little later Hilda came to me in the shop, complaining that she couldn’t get any salt on the bird’s tail. I told her that her steps were too short; that she must take very long and slow steps. Everyone, including the men coming in to eat, stopped to look and laugh at her efforts. Those little legs certainly stretched, but still no bird.

Inez was a most cheerful and lively person, as well as an excellent cook. One of our bulldozer operators, Herman Swanson, was a heavy drinker. He ate as much as two men and was big and fat. Inez kept telling him, “Herman, I’m warning you, you are digging your grave with your teeth.” He died in Point Barrow next winter.

I laid off all but two men in the fall. We cut and skidded big spruce logs to our shop and made go-devils into which we loaded our shop, mess house, parts warehouse, meat house, sauna, two bunk houses and the grocery storage building. I welded steel tongues for the go-devils out of heavy six inch pipe. Skids for the dragline came out of old 60 cat track rails and a tongue out of six inch drill casing. Thirteen units, counting the dragline and sleds, were loaded and ready to go just before Christmas.

On March fifteenth, 1950, with John Ogriz’s D-8 and operator to help us, we started moving as many loads as possible on the day shift. The night shift would go back and bring the rest. I went ahead on snowshoes every day, making a trail for the crew to follow. The weather turned warm so the snow packed.

One D-8 could pull the forty-five ton dragline on level ground because we kept it last on the cat train to have a hard packed trail. Up hills and steep pitches two D-8s had to be used and on some hills three were needed.

On the second day out of Moore Creek I was showshoeing three miles ahead when Jim Jokela came with one of the cats to tell me that the dragline had broken through and was in the swamp, sunk to the top of the tracks in the decomposed moss and mud. The weather had turned very cold again and was now twenty five below zero with the wind blowing a gale.

I suggested using the 60 with its bulldozer for a scoop, pulling it ahead with one D-8 and back with the other. So doing, we dug a sloping trench in front down to the bottom of the tracks. After putting spruce poles side by side crosswise up the slope, we covered them with snow and water. It froze hard that night. The next morning we pulled out the drag cable, hooking to a D-8 with the bulldozer blade down hard in the ground.

When I started up the dragline engine and pulled in on the drag cable, the front end of the machine sank deeper in the mud. No good.

I had left the gasoline engine in the dragline only to help if we got stuck. It did not help so we pulled it out. There is lays to this day in the swamp.

We had a new caterpillar Diesel engine on the bank of the Holitna River with the rest of our supplies. By rigging a four-part cable line from the cat to the dragline, one cat pulled it up the ramp easily.

We reached Sleetmute in two weeks, to run into a problem. The Kuskokwin River was sixty feet deep and about three hundred feet wide with only thirteen inches of ice. After making a snow dam across the river with shovels, we laid brush, poles and snow above the dam about forty feet wide, pumping water over it all, building it up approximately five inches each day so it froze solid every night. In a week the ice bridge was solid. To test it, the old 60 was sent across slowly in low gear by itself and back again. Both D-8s, hooked to a heavy load with a long cable, were send across in the same manner until all the loads were safely across.

At Nick Mellick’s trading post a decision was made to go as far as the Holitna River, taking only what loads could be pulled at one time. Over the big hill on the river flats, in chopping a hole through the moss, I found it frozen only six inches. A ten foot pole easily went down full length into the decomposed moss. But the frozen six inches was so full of roots that by leaving the snow on, it held up. The scrub spruce trees on both sides shook and swayed as we rumbled through.

Close to the Holitna River the crew waited while I set out to locate our supplies. I did not know if they were above or below us. After snowshoeing two miles down stream and back, there they were, just above on the opposite side.

By drilling, we discovered the ice to be only twelve inches thick, with fourteen feet of water, because of steaming hot springs upstream. We found a place that was two hundred feet across with only six feet of water and a little thicker ice. Taking the fan belts off the D-8, sealing the crankcase vent so no water could get into the engine, and hooking a long cable to a go-devil, I started across to get fuel oil to go back to Sleetmute. About two thirds of the way across, the whole river seemed to cave in. On the other side, under the snow, was a two foot cutbank. To climb the bank, I backed up, dropping the blade and pushed a huge pile of gravel to make a slope. This put the engine completely under water. I was nearly up to my shoulders. A Diesel engine will run under water if none gets inside. Not wanting to be half submerged again, I left that D-8 on the other side, but we pulled enough fuel across with a long cable.

When Nick Mellick told us that the ravine had never glaciered, the decision was made to leave the dragline and some of the loads until next spring, and take only what would be needed for mining.

When work ended in 1949 Inez insisted that she would fly to Sleetmute and cook for us on the trip. She was there waiting. It was a great help for us to have good hot food from then on. She was a wizard at cooking while the mess house was weaving and swaying. I put a steel railing around the top of the stove to keep the pots from sliding off.

Back at the river I drove our other D-8 across in the same place. By laying brush and poles on the ice in another spot we were able to send the 60 with its gas engine across without breaking through, then pull all the loads across with a long cable.

It was still forty miles to our mine. Having several round trips to make, we had to hurry, because the weather was turning warm, threatening to open up the many creeks that had to be crossed. On our last trip they were running wide open. By hooking two D-8s to each load we kept from getting stuck on the gravel bottoms.

A lot was to be done before actual mining could commence. A mile-long ditch for sluicing water had to be surveyed and dug, the camp buildings set up, cats to be repaired, pipeline and boxes to be put in. It was slow going without the dragline to dig the bedrock drain and the slope for the boxes.

I was please when school ended and Hildur, Ray and Hilda came. Having the family near made camp life much more pleasant.

On Bedrock with our first cut, I anxiously began panning, and was disappointed to find the ground very pour, with no nuggets. Nick Mellick had shown us many in his sample bottle of gold which he said came from hand dug holes on the creek. He lied to us. After working hard all summer we did not take out quite enough to pay for the long move and the summer’s expenses.

The area was overrun with black bears. At night they came to camp, trying to get into the screened meat house where smoked hams and bacon were hung.

One night in June about two A.M. Hildur was awakened by a scratching on the door. On Opening it, she was face to face with a big black bear, standing with its paws on both sides of the screen door. She screamed waking up Inez in the mess house next door. I jumped up, put my hat on, grabbed the gun, and ran out barefoot. Inez was standing on the mess house porch. As I ran down the hill, the open flaps on the rear of my long johns kept opening and closing. I got the bear and Hildur and Inez laughed the rest of the night.

Hildur and the children went back to school and I was lonesome for them. I called CQ and got an army radio operator on Ladd Field. He phoned Hildur and I had the one and only one-sided conversation ever with her. It was fun.

Back in Fairbanks I went to work at Ladd Field drilling water wells and ground test holes for the army Resident Engineers.

Mother died in November in an ambulance enroute to the hospital after going into a diabetic coma at home. Lempi and I flew to attend her funeral.

In March 1951 I again went to Taylor Creek with a crew of four men to get ready to go get the dragline and the rest of the loads.

I had a radio schedule with McGrath Radio each evening at seven P.M. One evening I received a message from the Army Engineers in Anchorage asking if we had housing for ten men. They would bring food and bedding. I answered O.K.

The next day a Canadian-made Beaver airplane came with five men; with five more the second trip. After that a B-17 bomber circled over camp. As it flew low over our airstrip, the bomb bay doors opened. Potatoes, vegetables, fruits, quarters of beef and even a bundle of brooms were scattered in the snow on the edge of the runway. I am sure we all gained at least five pounds during the following week because the Major generously invited us to eat with him and his men.

The ten men went up Taylor Mountain and found it to be an ideal place to build an early warning site to detect enemy aircraft. I made a deal with the major to haul the huge amount of building supplies and equipment from our river landing for forty dollars a ton, and each spring to haul up the oil and materials to operate the facility. They wanted us to bring our drill from Sleetmute as soon as possible, for they had to start drilling at the base of Taylor Mountain for water well.

Leaving them at our camp we headed for Sleetmute and found the Holitna River had only twelve inches of ice again. Picking a spot with a cutbank about twelve feet high on our side and a gravel bar on the other, we started bulldozing, first big trees for the bottom, then snow and willows. The large trees let the water through, preventing a dam forming. Raising the bulldozer blades high each time, we went over the bank, making a steep upgrade, so the bulldozer wouldn’t nose down and slide into the river when the ice broke and our fill settled. It took us all night and most of the next day to fill in the river, but by then a freight train could have crossed.

At Sleetmute a sorry looking mess greeted us. The ravine had glaciered for the first time ever, and the dragline was encased in solid ice to the top of the tracks. The sleds under the pipe loads were buried too. It was a week’s work picking and shoveling the ice.

On returning to camp we found a note on the table from the Major saying he had found a site closer to Anchorage. I was very disappointed as is would have been a money making deal for us. Besides hauling the supplies, they would have rented our equipment.

I got the new engine installed into the dragline and started mining on the twentieth of June. But even though the ground was only an average depth of ten feet to bedrock, all thawed, with no big rocks and only about a foot of muck on the top, we could not make a profit because the ground was so poor.

About a month before freezeup, John Ogriz came, saying he went broke at Slate Creek. He stayed until we closed down for good, as I thought. But John took it in his head to go there the next summer, putting us still deeper in debt.

The miners were closing down one after the other after World War Two because of the high prices on fuel and other supplies, with the price of gold still only thirty five dollars an ounce.

Gus had good ground in Ophir and was making some money. He made a deal with us all to buy the Taylor Creek outfit for the debts. He sold it later and made a small profit.